October 28, 2020

Appraising Homelessness in Toronto (F. Shrafat)

By Fatima Shrafat

An Appraisal of the Response to Homelessness in Toronto

Executive Summary:

The Fred Victor Organization determined that on any given day, over 9,200 people in the city of Toronto meet one of the definitions of homelessness. Shelters in the city generally reach an average occupancy rate of approximately 98% every night, and 76% of the homeless population claim that the key factor in improving their situation is ‘aid and accommodation in paying the high rents of the city’.

The following paper outlines the ongoing epidemic of homelessness in the city of Toronto, currently existing proposals or initiatives to combat this largely social issue, and what can be improved for a better future. These programs are simultaneously summarized, and critiqued. They are claimed as ineffective for their lack of results, as well as the potential long-term risks of not including rehabilitative services tied along with housing. A fundamental lack of supplied resources, and the dependence of homeless shelters on the government are also cited as problematic.

The issues with current affordable housing programs and their lack of success are further elaborated on through the lense of interviews conducted with three figures in the field of affordable housing. Cathy Crowe, a homeless advocate, Richard Dunwoody, a businessman and generator of the shelter initiative known as Project Comfort, and James Ries, an urban developer from California, were all directly consulted to provide their perspectives on this issue.

The HousingTO 2020-2030 Action Plan put forth by the city of Toronto is also addressed, and critiqued for similar reasons, namely: high costs with insufficient results, and motivations that deviate greatly from the principle of empathy. James Ries speaks from the perspective of a developer, and as he speaks of the mass homelessness in California, we are forced to look closer at our own crisis in Ontario. He states that the primary factors in improving the situation would be streamlining housing projects, and providing the correct incentives to spur market stakeholders into action.

A clear break-out of current cooperatives in the Spadina Fort-York district of Toronto is given and evaluated in terms of building type, provider type and unit size as well. In a depiction of Ward 10, or the Spadina Fort-York riding, approximately 29 community housing locations were found to exist in the area. As well as this, Toronto has been the city with the highest population in Canada as of 2020, this being approximately 6,196,731 people, with an annual growth rate of 1.10%.

We go on to assess the present status of housing in the City, costs of living, the feasibility of cooperative housing during a time of economic decline, and how this decline poses a significant problem to housing development. The Ontario Community Housing Renewal Strategy also proved useful in evaluating this epidemic. As acknowledged by the provincial government, there is a strong lack of coordination and communication between the community housing system, and other accessible housing systems. Support services for tenants are also often either unavailable or insufficient.

Overall, what has been found is that there are not enough alternative solutions, nor a sufficient amount of incentives for stakeholders in order to begin improving the living conditions of vulnerable people in the City. There is a lack of coordination in the process, and a scarce amount of conversation. As stated by Dunwoody:

“What do you do when you have a complex issue? In business, that means you address it– you bring people into solving it, and you stop referring to it as a “complex issue”.

Homelessness and Supportive Housing in Toronto:

1

As stated by the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness (COH), the term ‘homelessness’ officially “[describes] the situation of an individual, family or community without stable, safe, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate prospect, means and ability of acquiring it. It is the result of systemic or societal barriers, a lack of affordable and appropriate housing, the individual/household’s financial, mental, cognitive, behavioural or physical challenges, and/or racism and discrimination” (COH, 2012). This definition encompasses a range of living situations, which can include 1) Unsheltered living, which refers to a situation of absolute homeless, and living in public or private spaces that are either unintended for permanent human habitation, or that are unconsented and uncontracted for their use; 2) Emergency sheltered living, which refers to an often temporary place of shelter, including overnight shelters, women’s shelters, and interval houses; 3) Provisionally accommodated living, in a situation of indefinite accommodation and temporary stability, such as with interim housing, rental accommodations, refugee situations, or non-permanent housing scenarios; 4) In risk of homelessness, where the individual is not yet defined as ‘homeless’, however their present socio-economic state and condition of living is precarious, and does not meet provincial public health and safety guidelines.1

On any given day, over 9,2000 people in the city of Toronto meet one of these definitions of homelessness. As released in CPJ’s Poverty Trends 2017, approximately 4.8 million people in Canada lived in poverty as of 2017, with Toronto having the highest rate of poverty among major Canadian cities; a percentage of 17.0%.2

When looking at occupancy, and the quantity of homeless shelters in the city in wake of COVID-19, it has been reported as of August 6 2020, that a total of 2,071 homeless individuals occupy the shelter programs exist in Toronto, ON. The capacity potential for these shelters was 4,337 pre-COVID-19. As for family shelters, there is a current sum of 1,612 people occupying these locations, with a pre-COVID capacity of 766. With regards to the nine locations defined as ‘allied services’, there is a total occupancy of 265 homeless individuals. As stated in a personal interview conducted with Canadian homeless advocate and “street nurse” Cathy Crowe, “Homeless people have been last when it has come to federal, provincial, municipal strategies when it comes to protection, and with respect to COVID.”

She went on to speak of both the conditions that homeless people face with regards to the pandemic, and the exclusion when it comes to their safety:

“It was practically impossible for mass-testing to occur in homeless shelters before– there was a lot of finger-pointing between the city and the province, but they just never resolved it–it was really only around September 11 [2020] that the city mask bylaw (which did not apply to shelters and homeless people) included homeless people as well. They were then provided masks and required to wear them– but everything that we have been hearing about washing our hands, and socially distancing had not been at all made possible to this large population of people; workers in shelters had to wear masks but homeless people could not.”3

1 Gaetz, S.; Barr, C.; Friesen, A.; Harris, B.; Hill, C.; Kovacs-Burns, K.; Pauly, B.; Pearce, B.; Turner, A.; Marsolais, A. (2012) Canadian Definition of Homelessness. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press.

2 https://www.homelesshub.ca/resource/poverty-trends-2017

3 Crowe, C. (2020, Sept). Personal interview [Personal interview].

2

Shelters in the city generally reach an average occupancy rate of approximately 98% every night, and 36% of the homeless population in Toronto have been homeless for over one year. 76% of the homeless population claim that the key factor in improving their situation is ‘aid and accommodation in paying the high rents of the city’.4

As claimed by Crowe, “We have about 6,000-7,000 people in shelters, and after about six weeks of lobbying we only got a few portable toilets in a few places, stations to wash hands, it’s–clear exclusion, and it is a public health issue. It’s a social issue. It’s not rocket science.”

Despite Toronto adding 2,500 beds to its emergency system since 2016, the Toronto shelter system remains at or over its capacity more frequently than able to be sustained in the long term. A member motion put forward by the Toronto city council in 2018 set a target of 1,800 supportive housing units to be built each year for the next decade, in an effort to combat the epidemic of homelessness in Toronto.5

As of November 2019, 1,278 units were expected to be built for 2019, 2020, and 2021 combined. This falls incredibly short of the original target of 1,800 units per year. It is important to note that increasing the volume of supportive housing units in Toronto can also involve using facilities that are pre-existing, such as unoccupied community housing units or private rentable units with an addition of government subsidies to promote support. Something similar was done in British Columbia, where non-profit housing providers operate both isolated housing units, and single-room-occupancy hotels to provide non-clinical connections to primary health care, substance use services, and the like for vulnerable citizens of the province, including those that are homeless or at risk of becoming so.6

The lack of follow through with this initiative of building 1,800 new units of supportive housing was pointed out by both Cathy Crowe, and Richard Dunwoody, a businessman who started a program known as “Project Comfort” to contribute to improving the situation of homelessness in Toronto. As he claimed in a personal interview held with Dunwoody:

“The Open Door Policy in 2018– they announced that they were going to build about 100 modular housing by then; but there is no follow through, you announced it in 2018, and then something similar in 2019, and you committed to building these homes. It is 2020 and you are only now willing to build it. Where was this initiative before the pandemic? It’s only now that there is pressure put on it, that they are building homes to help about two hundred people in ten years.”7

Crowe had a similar statement to make as well. She also pointed out that “COVID exposed the direness of the situation; overcrowded, substandard housing, addiction– short-term band-aid solutions include rent supplements, purchasing hotels/empty units to use for single room occupancy, but we are not seeing a broader vision for people.”

4https://www.fredvictor.org/facts-about-homelessness-in-toronto/; https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/data-research-maps/research-reports/housing-and-homelessness-research-a nd-reports/ ;; https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/homeless-in-toronto-1.5400781

5https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-stuck-in-vicious-cycle-without-enough-supportive-housing-councillor -says-1.5372209

6 https://www.bchousing.org/housing-assistance/housing-with-support/supportive-housing 7 Dunwoody, R. (2020, Sept). Personal interview [Personal interview].

3

In February 2019, the 2019 Operating Budget Briefing8, which was provided by the General Manager, Shelter, Support, and Housing Administration (SSHA), to the Toronto Budget Committee, expressed that:

“Given Toronto’s expensive housing market and very low vacancy rates, use of existing rental housing stock for supportive housing is increasingly challenging. Locating properties that could be converted to supportive housing with available operating funding is an ongoing challenge.”

They also expressed that the planned construction of supportive housing in the city included:

- ● 200 Madison Ave – 61 housing units, using existing support services and rent subsidies provided by the supportive housing provider referral partners, opening in 2019. Capital funding provided through the City’s Open Door program and the federal/provincial Investment in Affordable Housing program.

- ● 25 Leonard St – 22 housing units in partnership with St. Clare’s Multifaith Housing, in a new building adjacent to their existing site, using existing support services provided by the agency and referral partners, opening in 2020. Capital funding contribution of $500,000 provided by the City.

- ● Housing units constructed through the City’s Housing Now initiative may be leveraged to create supportive housing with the addition of housing subsidies and operating funding for support services. These units will likely be operational by 2022-2024.As well as this, current initiatives underway to create supportive housing through acquisition and renovation of existing rental stock with addition of support services, include:

- ● Homewood Ave – 16 housing units in partnership with Na-Me-Res, using existing support services and rent subsidies provided by the agency, opening in 2019. Capital funding provided by the City and federal/provincial investment.

- ● 9 Huntley – 20 housing units in partnership with Fife House, using City operating funding through the George Street Revitalization project, opening in 2019. Capital funding provided by the City and federal/provincial investment.

- ● 419 – 425 Coxwell Ave – 12 housing units added to an existing social housing site, in partnership with New Frontiers Aboriginal Residential Corporation, using existing support services and rent subsidies provided by the agency, opening in 2020. City capital contribution through Open Door incentives.

- ● 389 Church – 120 housing units for women, with operating funding for support services and rent supplements provided through provincial Home for Good funding with a non-profit provider to be selected through a Request for Proposal process, opening in 2020. Capital funding through provincial Home for Good and City funding.

- ● 13 – 19 Winchester St – 36 housing units for women with operating funding for support services and rent supplements provided through provincial Home for Good funding, operated by Margaret’s Housing and Community Support Services, opening in 2020. Capital funding through provincial Home for Good and City funding.8https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2019/bu/bgrd/backgroundfile-124411.pdf;; https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2019/bu/bgrd/backgroundfile-126639.pdf

4

● St Hilda’s Towers – 301 housing units of existing social housing that will be modernized with Home for Good, IAH, SIF and National Co-investment capital funding. A provider(s) will be selected through an RFP process to provide support using existing resources.

As reported in the 2019 Operating Budget Briefing, there are also a number of initiatives underway to use existing rental stock for supportive housing. These have proved challenging to implement, given the low vacancy rates and limited availability of affordable rental housing in Toronto. Locating suitable properties for units has also proved challenging. These initiatives include:

- 1,500 people supported through the Home for Good program in 2018, with another 500 planned in 2019. This includes layering additional supports into non-profit housing provider units as well as rent supplement units in the private rental market.

- 204 rooming house units within the Toronto Community Housing portfolio that have been converted to supportive housing through the Tenants First initiative in 2018, with operating funding for support services through the provincial Home for Good funding. Approximately 140 existing tenants are currently being supported, and an additional 60 tenants will be housed once renovations to units are completed in 2019

- 130 housing units, with operating funding allocated by the City, for Habitat Services supportive housing in rooming houses, to support people from Seaton House for the George Street Revitalization project in 2019 (in addition to the 20 units operated by Fife House identified above, also part of the GSR project).However, it is important to note, when discussing supportive housing, that this initiative can often

be primarily centralized around disabled people, as well as those who are of low economic status but nevertheless have a source of income, or are in a transitory period of expecting income in the near future. Those considered homeless and particularly vulnerable, are often fully reliant on the initiatives and programs designed to support them. Supporting and rehabilitating a large population of people is often difficult from an economic perspective, especially at a federal level. Richard Dunwoody put it quite succinctly, stating that:

“Greater than 80% of the revenue of homeless shelters is provided by the city— if funding or revenue stops or is negated, they cannot possibly provide the support needed. Shelters are not at arm’s length and they are no longer independent– we have institutionalized compassion, and we have created so many rules and guidelines that there is no room for empathy.”

5

As written in the Toronto Housing Charter- Opportunities For All, ‘It is the policy of the City of Toronto that fair access to a full range of housing is fundamental to strengthening Toronto’s economy, its environmental efforts, and the health and social well-being of its residents and communities.’

As of December 2019, the city of Toronto put forth their HousingTO 2020-2030 Action Plan9, which includes the Housing Now initiative. This would be a collaborative effort between housing stakeholders, and the public. Among other things, this plan has the key objectives of: 1) enhancing eviction prevention measures, 2) maintaining and sustaining the Toronto Community Housing Corporation, 3) establishing a pipeline to support the creation of 40,000 affordable rental and supportive homes through a public/private/non-profit land banking strategy, 4) helping homeowners stay in their homes and purchase their first homes, and 5) supporting in-home care and long term care options for seniors.

Five actions would be taken by the city to facilitate the prevention of homelessness in Toronto, as stated in the plan:

Action 1– Focus on upstream interventions that prevent people from becoming homeless by:

- Developing and implementing innovative new eviction prevention and shelter diversionservices and strategies.

- Building on successful prevention approaches through extending and expanding theEviction Prevention in the Community (EPIC) program.

- Increasing coordination and integrated service approaches with federal and/or provincialchild welfare, corrections social services, immigration and health systems to reduce discharges into homelessness.

Action 2– Ensure an effective and housing-focused emergency response to homelessness by:

- Continuing to provide street outreach and overnight accommodation that offers a safe,temperature controlled indoor space and connections to other supports to meet theimmediate needs of people experiencing homelessness.

- Together with community partners, continuing to ensure that people experiencinghomelessness are provided client-centred, high quality, housing focused services.

- Continuing to implement the new housing-focused service model at new shelter sites andexplore opportunities to expand implementation to all shelters.

- Increasing partnerships with health service providers and improving coordination andintegration of health services within shelter, 24-hour respite and outreach services.

Action 3– Better connect people experiencing homelessness to housing and supports by:

- Implementing a coordinated access system that includes a by-name list of all peopleexperiencing homelessness, a common assessment approach, and prioritization ofpopulations with greatest needs.

- Developing a coordinated approach in partnership with the Greater Toronto ApartmentAssociation to encourage private sector landlords to provide more supportive and affordable rental housing options and help people maintain their housing.

9https://www.toronto.ca/community-people/community-partners/affordable-housing-partners/housingto-2020-2030-acti on-plan/ ;; https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/94f0-housing-to-2020-2030-action-plan-housing-secretariat.pdf

6

c. Building an integrated service delivery system and establishing data sharing protocols within the housing and homelessness sector to improve service planning and client-centred program delivery.

d. Developing and regularly reporting on specific performance indicators and targets that measure progress towards ensuring that when homelessness does occur, the experience is rare, brief and non-recurring.

Action 4– Increase availability of supportive housing by:

- Completing Council’s capital plan to provide an additional 1,000 shelter beds and shift allfuture investments toward developing permanent housing including supporting Council’starget of 18,000 supportive homes approvals over 10 years.

- Exploring opportunities to leverage existing shelter properties for development ofsupportive housing.

- Piloting innovative supportive housing opportunities with support from the federal,provincial governments and in partnership with the non-profit housing sector.

Action 5– Develop strategies and programs that meet the needs of specific populations by:

- Developing specific interventions for equity-seeking and vulnerable groups with specificneeds i.e. survivors of domestic violence, victims of human trafficking, LGBTQ2SAI+people, youth, seniors, people with disabilities, refugees and newcomers.

- Working with the youth services sector to develop and test effective youth homelessnessprevention strategies.

Implementing this plan would reportedly result in 18,000 new supportive home approvals for vulnerable residents of the city such as people who are homeless or at risk of being so, and the prevention of 10,000 evictions for low-income households through programs such as the City’s Eviction Prevention in the Community (EPIC) program. Along with this, 58,500 Toronto Community Housing Units would be repaired, the creation of 1,500 new non-profit long-term care beds would be supported, and 1,232 city-owned long-term care beds would be redeveloped.

7

Affordable Housing Initiatives:

The city of Toronto works with a range of groups, in the efforts of providing affordable home ownership opportunities to its citizens. These include Habitat for Humanity, Options for Homes, Toronto Community Housing and the Daniels Corporation, and Trillium Housing. Aboriginal purchasers are also suggested to contact the Miziwe Biik Development Corporation.

Along with this, there are multiple initiatives with the intention of improving the accessibility of housing in the city.10 Most notable of these initiatives is modular housing. A partnership between the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, and the city of Toronto, has produced a program to aid Toronto’s homeless populations. The intention is to build about 250 modular housing units, with 110 units having been expected to have been built by September 2020, and another 140 units by early 2021.11 A few noted benefits to this form of housing were stated as:

- ● Faster construction times, meaning that housing can be built quickly when needed most, providing homes for people experiencing homelessness or during a crisis, for example

- ● Quick and easy installation on a variety of sites, such as tight urban properties, environmentally sensitive sites and remote rural areas

- ● Indoor, climate-controlled manufacturing environments that allow construction to take place year-round without the delays and extra costs associated with extreme weather and temperature changes

- ● The reduction of material losses and theft, since manufacturing facilities tend to be more secure than construction sites

- ● The use of precise manufacturing equipment and processes that can improve air-sealing and overall quality controlThe project is funded by the Affordable Housing Innovation Fund, which is a $200 million dollar fund that is instrumental to the National Housing Strategy in Canada. This strategy involves a $55 billion dollar, ten-year plan which claims to have the objective of reducing homelessness in Canada by 50% through financial contributions and low-interest loans. It promises to create 125,000 new housing units and lift 530,000 families out of housing need, as well as repair and renew more than 300,000 housing units.However the costs of this supposed “cure-all” were summed up by Richard Dunwoody as well. “It costs about 6,000$ to build a container housing unit. However it costs the city about 4,000$ a month to put someone in a shelter. My compassion is around helping the vulnerable people in the community– What do you do when you have a complex issue? In business, that means you address it– you bring people into solving it, and you stop referring to it as a “complex issue”. Particularly with municipal politicians and the community, they have had this issue for about ten years, and nothing has been remedied.”10 https://www.toronto.ca/community-people/community-partners/affordable-housing-partners/11https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/housing-observer-online/2020-housing-observer/building-housing-quickly-when-mat ters-most ;; https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/media-newsroom/news-releases/2020/financial-stability-help-canadians-results-q1-2 020

8

With regards to offering housing, the most popular and promoted form of providing aid is through rental assistance. However, it is vital to take into account that programs which span for years over time will not provide the rapid, efficient action that is needed to improve the current situation at large. In an opportunity to speak to James Ries, a member of the Santa Monica Planning Commission from the state of California, quite a lot of his information was useful, and incredibly relevant to the epidemic seen in Toronto, which is similarly urbanized and highly-populated. Ries has been involved with a number of affordable housing projects while also working in land entitlements and urban development.

In an personal interview conducted with him, Ries provided a clear break-out on homelessness in large cities from the perspective of a developer:

“[Homelessness] is pervasive, every community feels that they are being inundated more than other communities with homelessness, but they are not looking at the underlying issues of economic stability and housing– I don’t think that there is one silver bullet, we need a lot of alternatives. I have seen houses in the community built from shipping crates that save time on development and through being modular in nature, but these units are not just housing individuals. They are also building services in with the ground for these projects.”

Ries continues to speak of the importance of rehabilitation as a counterpart to housing when aiding vulnerable populations:

“I come with the perspective of someone in the developer industry. If you could streamline the housing and provide the right incentives— another thing that happened in the city, there was an initiative that took place where the city planning department was able to create a series of incentives that incentivized market rate developers to include anywhere between 8% (low-income) to 11% (very-low income) of their total units in a project.

Density increases were big enough that market developers wanted to do it. However, we could have a problem later, in the long-run, because these projects were not always tied with services to get them back on their feet. There needs to be rehabilitation as well.”

Looking back to the HousingTO 2020-2030 Action Plan as previously mentioned [see: Homelessness and Supportive Housing in Toronto] , the Housing Now initiative expects to be “affordable for households earning between approximately $21,000 and $56,000 per year”. This initiative has two primary components: Phase 1 and Phase 2. The first phase was estimated previously to have the potential to create about 10,000 new residential units in Toronto, with 3,700 affordable rental units. Based on the work having been done on Phase 1, it is estimated to create roughly 10,750 units, with 7,800 being purpose-built rental housing and 3,900 being defined as ‘affordable rental units’. Phase 2 was approved by the city in May 2020, and involves six new building sites, for a total of 18. This expects to generate 1,455-1,710 new residential units, with 1,060 to 1,240 purpose-built rentals. Half (530-620) will be considered ‘affordable rental units’.

9

Potential options for these six recommended building sites are, as listed by Urban Toronto12:

• 158 Borough Dr.– Located on Scarborough Town Centre lands adjacent to Scarborough Civic Centre Library. Currently a landscaped grass lot.

• 2444 Eglinton Ave. E.– Located on Eglinton’s north service road, adjacent to TTC staff/commuter parking for Kennedy station. Currently home to a single-storey City-owned commercial building.

• 1627 & 1675 Danforth Ave.– Located just east of Coxwell on the south side of Danforth. Currently home to the TTC Danforth Garage and Danforth-Coxwell Public Library, and site of the future consolidated Toronto Police Service 54/55 Division.

• 1631 Queen St. E.–Located just east of Coxwell on the south side of Queen. Currently home to a City of Toronto Social Services office.

• 405 Sherbourne St.– Located just north of Carlton Street on the east side of Sherbourne. Currently home to a Green P parking lot.

• 150 Queens Wharf Rd.– Located immediately north of the Library District condos development in the CityPlace area. Currently a vacant lot.

12 https://urbantoronto.ca/news/2020/05/phase-2-housing-now-initiative-create-new-affordable-homes ;; https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/94f0-housing-to-2020-2030-action-plan-housing-secretariat.pdf

10

The Status of Community Housing:

As compiled by the city of Toronto, the following is an appendix which clearly maps the quantity of subsidized housing units that fall under the guidelines of Spadina-Fort York District. This is defined as an area being bounded in the west by Parkdale-High Park, and in the east past Mill Street. The northern area of the district is goes along Dovercourt Road to Dundas Street West13.

Appendix A:

Appendix B:

As shown by this depiction of Ward 10, or the Spadina Fort-York riding, approximately 29 community housing locations exist in this area.

13 https://ontario.coop/find-co-op ;; https://www.elections.ca/res/cir/maps2/mapprov.asp?map=35101&lang=e

11

The following table [PART A] indicates the address of these locations, the building types and provider types, as well as the unit size(s) and map number:

| NAME | ADDRESS | BUILDING TYPE | PROVIDER TYPE | UNIT SIZES | MAP NUMBER |

| QUEENS QUAY WEST | 679 QUEEN’S QUAY WEST, TORONTO, M5V 3A9 | High Rise | Toronto Community Housing | Bachelor, 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom |

310 |

| HARBOUR CHANNEL HOUSING CO-OP INC | 633 LAKE SHORE BOULEVARD WEST, TORONTO, M5V 3B9 | High Rise, Townhouse/ Walk-up | Co-Op | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom | 562 |

| BATHURST QUAY | 25 BISHOP TUTU BOULEVARD, TORONTO, M5V 2Z9 | High Rise, Townhouse/ Walk-up | Toronto Community Housing | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom,4 Bedroom | 199 |

| THE RAILWAY LANDS (TORONTO COMMUNITY HOUSING CORPORATION CM) | 150 DAN LECKIE WAY, TORONTO, M5V 0C9 | High Rise, Low Rise | Toronto Community Housing | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom,4 Bedroom, 5 Bedroom | 753 |

| BATHURST/ADELAIDE PROJECT | 575 ADELAIDE STREET WEST, TORONTO, M6J 3R8 | High Rise | Toronto Community Housing | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom | 224 |

| NIAGARA NEIGHBOURHOOD HOUSING CO-OPERATIVE INC | 180 NIAGARA STREET, TORONTO, M5V 3E1 | High Rise | Co-Op | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom | 561 |

| 63 MITCHELL | 63 MITCHELL AVENUE, TORONTO, M6J 1C1 | Low Rise | Toronto Community Housing | 3 Bedroom | 508 |

| ARTSCAPE NON-PROFIT HOMES INCORPORATED | 900 QUEEN STREET WEST, TORONTO, M6J 1G6 | Low Rise | Private non-profit | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom. NOTE: Mandate- Artist |

951 |

12

| TERRA BELLA FAMILY COMPLEX (Terra Bella Family Complex Corporation) | 24 SHAW STREET, TORONTO, M6J 3W1 | High Rise | Private non-profit | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom | 303 |

| ALEXANDRA PARK APARTMENTS | 91 AUGUSTA AVENUE, TORONTO, M5T 2L2 | High Rise | Toronto Community Housing | Bachelor, 1 Bedroom | 221 |

| ATKINSON HOUSING CO-OP | 71 AUGUSTA SQUARE, TORONTO, M5T 2K5 | High Rise, Low Rise, Townhouse/ Walk-up | Co-Op | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom, 4 Bedroom, 5 Bedroom | 222 |

| QUEEN/VANAULEY PROJECT | 20 VANAULEY STREET, TORONTO, M5T 2H4 | High Rise, Townhouse/ Walk-up | Toronto Community Housing | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom | 220 |

| LARCH STREET | 15 LARCH STREET, TORONTO, M3M 4M4 | Townhouse/Wa lk-up | Toronto Community Housing | Bachelor, 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom | 309 |

The following table [PART B] indicates the address of the remaining locations, the building type of the units, the provider type, as well as the unit size(s) and map number:

| NAME | ADDRESS | BUILDING TYPE | PROVIDER TYPE | UNIT SIZES | MAP NUMBER |

| SULLIVAN PROJECT | 11 SULLIVAN STREET, TORONTO, M5T 1B8 | Townhouse/ Walk-up | Toronto Community Housing | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom | 217 |

| 190 JOHN STREET | 190 JOHN STREET, TORONTO, M5T 3E5 | Low Rise | Toronto Community Housing | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom | 461 |

| MCCAUL STREET PROJECT | 22 MCCAUL STREET, TORONTO, M5T 3C2 | High Rise, Townhouse/ Walk-up | Toronto Community Housing | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom | 325 |

| BEAVER HALL ARTIST’S CO-OPERATIVE INC. | 29 MCCAUL STREET, TORONTO, M5T 1V7 | High Rise | Co-Op | Bachelor, 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom NOTE: Mandate- Artist; Visual |

750 |

13

| SIMCOE STREET | 248 SIMCOE STREET, TORONTO, M5T 3B9 | High Rise | Toronto Community Housing | Bachelor, 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom |

324 |

| 111 CHESTNUT | 111 CHESTNUT STREET, TORONTO, M5G 2J1 | High Rise | Toronto Community Housing | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom | 225 |

| THE ESPLANADE | 55 THE ESPLANADE, TORONTO, M5E 1V2 | High Rise | Toronto Community Housing | Bachelor, 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom, 4 Bedroom |

228 |

| OLD YORK TOWERS (ST. LAWRENCE NEIGHBOURHOOD SENIORS NON-PROFIT HOUSING) | 85 THE ESPLANADE, TORONTO, M5E 1Y8 | High Rise | Private non-profit | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom | 481 |

| 1 CHURCH STREET | 1 CHURCH STREET, TORONTO, M5E 1Y6 | Townhouse/ Walk-up | Toronto Community Housing | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom, 4 Bedroom | 579 |

| OWN HOUSING CO-OPERATIVE INC | 115 THE ESPLANADE, TORONTO, M5E 1Y7 | High Rise | Co-Op | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom | 482 |

| NEW HIBRET CO-OPERATIVE HOMES INC | 2 MARKET STREET, TORONTO, M5E 1Y9 | High Rise | Co-Op | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom | 553 |

| CROMBIE PARK | 49 HENRY LANE TERRACE, TORONTO, M5A 4B5 | High Rise, Townhouse/ Walk-up | Toronto Community Housing | Bachelor, 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom, 4 Bedroom |

231 |

| SCADDING COURT | 15 SCADDING AVENUE, TORONTO, M5A 4G6 | High Rise, Townhouse/ Walk-up | Toronto Community Housing | Bachelor, 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom | 236 |

| ST. LAWRENCE TOWNHOUSES | 10 AITKEN PLACE, TORONTO, M5A 4E5 | Townhouse/ Walk-up | Toronto Community Housing | 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom | 498 |

| LA PLACE ST. LAURENT (LES CENTRES D’ACCUEIL HÉRITAGE) | 33 HAHN PLACE, TORONTO, M5A 4G2 | High Rise | Private non-profit | 1 Bedroom, 2 Bedroom, NOTE: Mandate- Seniors; 59+, French speaking | 237 |

14

| NEW CANADIANS FROM THE SOVIET UNION | 5 HAHN PLACE, TORONTO, M5A 4S1 | Townhouse/ Walk-up | Private non-profit | 2 Bedroom, 3 Bedroom, 4 Bedroom | 598 |

As stated by Councillor Joe Cressy, who represents Ward 10, Spadina Fort-York, “Despite the reality that the City of Toronto cannot completely solve the crisis alone, without more support from our government partners, we must do everything possible with the resources at hand.”14

The Councillor suggests that one of these aforementioned ‘resources’ could be leveraging city-owned parcels of land for new affordable housing construction. Block 36 North, for example, is the last block of undeveloped land in CityPlace, which is immediately north of the Fort York library branch in Toronto. Block 36 North is located in the Railway Lands through the then-new Open Door Program (EX10.19). This area can also be seen as indicated in [Part A] of the previously given tables. This area is owned by the City of Toronto and a target for new affordable rental housing. Councillor Cressy, and the Toronto City Council approved the area for construction in 2016 however the future of this item is currently uncertain.

The Status of Housing:

Note: The following numbers represent an estimate of what it costs to live in Toronto. While it is possible for people to live in Toronto for lower, or higher amounts, the following serves as a reflection of the average individual living in the City.

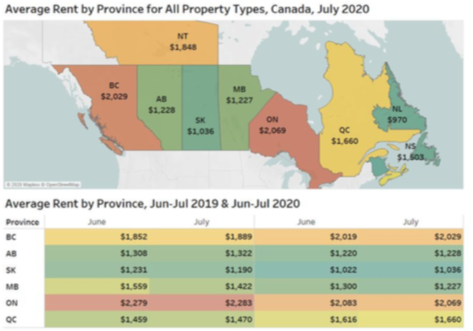

In terms of the August 2020 Rent Report collected by Rentals.ca, The average rent for all Canadian properties listed on this site in July was $1,771 per month, down 8.1% annually. For the first time since September 2019, the average rent increased on a monthly basis, rising by $1. The median rental rate was $1,700 per month in July, down 6.8% annually, but unchanged month over month.15 In terms of national renting rates, Toronto had the highest cost of rent, at an average of 2,051$ for a one bedroom apartment, and 2,709$ for a two bedroom apartment unit. This far exceeds the mean cost for these apartment units when taking into account thirty two cities in Canada. This mean cost for a one bedroom apartment is 1,411$, and for a two bedroom apartment it is 1,775$ as of August 2020.

As well as this, when looking at the provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec, the province of Ontario has the highest rent on average, as shown for June and July of 2019, and 2020.

14 http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2020.PH13.8 ;; http://www.joecressy.com/building_new_affordable_housing_in_cityplace

15 https://rentals.ca/national-rent-report

15

The following graphic taken from the August 2020 Rent Report is further indicative of this margin between provinces:

The average cost of rent in the province has shown to decrease slightly from 2019, however still remains far more expensive than others. The average rent for Ontario as of June 2019 was 2,279$ and then 2,283$ as of July 2019. For these same months in 2020, the average rent is 2,083$ and 2,069$.

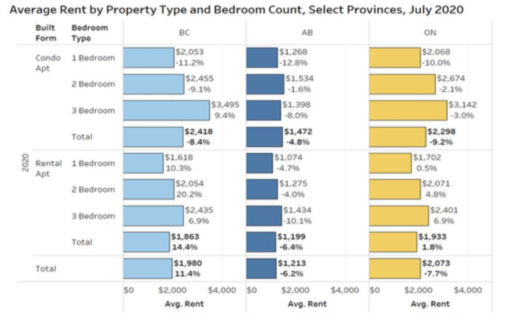

A similar graphic, as shown by the same report, gives regard to the bedroom types and form of building, when looking at the provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario:

16

When taking account more than the fees for the housing itself, the financial rate comparison site LowestRates.ca was consulted for its 2020 Cost of Living Index16. Factors such as transportation, basic needs such as food, health and fitness, as well as necessities such as internet access and entertainment, only makes the cost of living in the City more expensive. Their report determined that:

- ● Renters who take public transit will spend $3,541.24/month, or $42,494.88 annually

- ● Renters who drive will spend $3,840.23/month, or $46,082.76 annually

- ● Homeowners who take public transit will spend $5,415.73/month, or $64,988.76 annually

- ● Homeowners who drive will spend $5,714.72/month, or $68,576.64 annuallyHowever, when looking at the present tax rates of Ontario, and Canada as a nation, and the amount of money necessary to live a stable life in Toronto, the following was shown in this report:

- ● Renters who take public transit will need to earn $55,500 before tax ($42,584 after tax)

- ● Renters who drive will need to earn $61,000 before tax ($46,376 after tax)

- ● Homeowners who take public transit will need to earn $88,000 before tax ($65,056 after tax)

- ● Homeowners who drive will need to earn $94,000 before tax ($68,971 after tax)When looking at the other factors which must equally be included when calculating the expenses of daily life when living in the City, this is an approximation of the costs one must pay to live:

- ● Homeowner housing costs average $4,223.56/month

- ● Renter housing costs average $2,349.07/month

- ● Public transit costs average $258.55/month

- ● Driver costs average $557.54/month

- ● Food costs average $533.95/month

- ● Cell Phone and Internet costs average $155.96/month

- ● Entertainment costs average $178.96/month

- ● Health and fitness costs average $64.75/monthGenerally, as shown by the Toronto-based transport and moving service High Level Movers17, when purchasing a house in Toronto, the price per square meter in City Centre comes at C$7000.00, whereas Price per square meter outside of the City will cost you about C$5248.83. Toronto can, therefore, be considered one of the most expensive areas to live in, and there is a detrimental shortage of affordable housing, which becomes even more a cause for concern when looking at the population of the area. As of 2020, as shown by the Toronto Census Profile, Toronto has been the city with the highest population in Canada, which is listed as 6,196,731 people. It also has an annual growth rate of 1.10%, and is the fourth most populated city in North America.1816 https://www.lowestrates.ca/cost-of-living/toronto ;; http://eyetfrp.ca/affordable-housing-list/17 https://highlevelmovers.ca/what-is-the-cost-of-living-in-toronto/

18 https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/toronto-population

17

Feasibility Regarding Cooperatives:

As described by the Ontario Community Housing Renewal Strategy, community housing is absolutely vital to the ecosystem of a city. In the province of Ontario, almost 20% of purpose-built rental housing is community housing. The insured replacement value of community housing is over $30 billion without including the monetary value of the land. Community housing can be defined as “housing owned and operated by non-profit housing corporations, housing co-operatives and municipal governments or district social services administration boards. These providers offer subsidized or low-end-of market rents- housing sometimes referred to as social housing and affordable housing.” 19

Social housing has been developed through federal or provincial government programs since the 1950s. Over 250,000 households live in social housing, and about 185,000 pay a rent based on their income while the remainder pay a moderate market rent. Affordable housing programs that have spawned since the early 2000s have led to the construction of about 21,800 rental units with rents maintained at or below 80% of Average Market Rent for at least 20 years. These units were built in both the community and market sector.

According to Statistics Canada, between 1991 and 2016, the number of Ontario households needing assistance increased from approximately 12% to 15% of total households. As of now, approximately 56% of renter households in the province cannot afford the average rent for a 2-bedroom apartment. Sharp increases in these costs are especially detrimental to low-income households that populate the province.

The main problem is that a lot of housing stock either need significant repairs, and have been taken out of use or relevance because of its poor conditions, or face the issue of financial uncertainty when continuing to offer cooperative housing after the original time-frame and obligations of their program ends. There is a strong lack of coordination and communication between the community housing system, and other accessible housing systems. Support services for tenants are also often either unavailable or insufficient. The overall process needs to be organized and streamlined, more opportunities need to be consistently generated and non-profit, co-op, and municipal rental supply needs to be fundamentally increased.

Adequate opportunities that fit the needs of the individuals being housed is also invaluable. Firm partnerships, and private market landlords are also often important to this cause. Rent supplement agreements organized with these landlords aid with providing ongoing access to affordable units for households on social housing waiting lists, or individuals in need of supportive housing.

James Ries, in his interview regarding the epidemic of homelessness in California claimed that other issues when it comes to housing are a lack of supply, and a lack of rehabilitative services embedded in a housing program as well. He also spoke of the gentrification involved with urbanization, and went on to express that, “[He does not] think that [they] could build enough housing to have a massive impact at this moment. The process is very cumbersome. It takes about five years for you to see any active building– the economy going south, and COVID-19 is not helping us– the process is still arcane; getting through developments, and the costs are very high— an average of about 530,000$ per unit; we just couldn’t begin to solve this problem.”20

19https://www.ontario.ca/page/community-housing-renewal-strategy?_ga=2.215011103.920690543.1558014142-128 9387729.1520869731

20 Ries, J. (2020, Sept). Personal interview [Personal interview].

18

As stated by the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing of Ontario, “Municipalities are the biggest contributors to community housing, with support from the federal government and the province. The province is the primary funder of homelessness services, with some municipalities making a large contribution and some communities receiving federal funding as well. The province is the primary funder of supportive housing programs, which combines subsidized housing with support services”. However in opposition to this, Richard Dunwoody spoke of intervention as crucial to understanding homelessness as an inherently social issue, “I think that we cloud the issue. Here is my statement, and my background is in business— the number one issue is that people are homeless because of government intervention. Often within politics, interest must be genuine- rooted in principle, and not [political] parties.”

The total spending of the government at a municipal, provincial, and federal level, can be broken down to provide a clear indication of the amount spent at each level on community housing, homelessness, and supportive housing. The following chart, as provided by the Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing provides an approximation of the spending at each of these three government levels, from between the years of 2014-15 to 2017-18:

Due to the amount of co-op housing in Toronto, ON, rather than place the database of co-ops in an appendix, the following links to two (2) co-op directories based around Toronto have been provided. Within these directories, co-ops are described with an inclusion of their address and location, as well as further information on the units they contain and their prices. The first database given, “Database A”, provides the information for 276 cooperative housing locations in Toronto. “Database B” provides the information for 180 cooperative housing locations in Toronto.

Database A: Canpages Cooperatives in Toronto:

https://www.canpages.ca/business/ON/toronto/cooperatives/3844-215200-p5.html

Database B: Cooperative Housing Federation of Toronto:

https://co-ophousingtoronto.coop/co-op-directory/

| GROUP | MUNICIPAL | PROVINCIAL | FEDERAL |

| Community Housing | 54% | 11% | 35% |

| Homelessness | 23% | 69% | 8% |

| Supportive Housing | 0.50% | 99% | 0.50% |

19

Areas to Innovate, and Pre-Existing Solutions:

In 2017, the Common Cause Foundation for Co-operatives UK compiled an index created in order to determine a succinct response to the question ‘what are the most cooperation-minded countries from a global standpoint?’.21 This study assigned 88 countries a “co-operative value score” towards their tendencies towards both a) universalism and b) benevolence. With this regard, among the highest ranked countries were Brazil, Norway, Uruguay, and Canada. However, some key observations to note are that the countries that were more dominated by a desire to fore-mostly monopolize wealth and power, or those where the levels of security or stability were lower, tended to have the least amount of co-operatives. Something to consider is whether it is the values and state of a country which affects the amount of co-operative initiatives it has, or if the country itself is influenced by its organizations and molded in that direction. A kind of ‘the chicken or the egg?’ scenario, as it were.

PricewaterhouseCoopers, or “PWC”, is a network of taxation and accounting firms, that in partnership with the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) CEO 2015 Conference, made a list of the best cities in the Asia Pacific region to live and do business.22 They were ranked based on characteristics, and 39 indicators which were divided in sections which included factors such as environmental sustainability, and economics. In this list, Toronto was ranked first, followed by Vancouver, Singapore, Tokyo, Seattle, Auckland, Seoul, Melbourne, Los Angeles and finally Osaka. Toronto’s rank was based primarily on its open government and tolerance as a community. However, when regarding co-operatives in these highly esteemed and populated cities in the world in both an economic regard and a social one, it is important to measure Toronto against other highly-populated cities on this list.

Co-op Housing International (CHI) provided statistics on a variety of countries in the world, and their success with regards to cooperative housing and affordable housing. According to their data, Canada had a population of 37.3 million people in 2019. We also had 2,212 housing co-ops, which built about 92,526 units as of last year. About 250,000 people also lived in housing co-operatives at this time, and our housing stock was a total of 14,072,080 dwellings in 2016.23 The United States, in comparison, had a population of 329.3 million in 2019, and 6,400 housing co-operatives with 1,200,000 dwellings divided into 425,000 limited or zero equity dwellings, and 775,000 market rate dwellings. Their housing stock was a total of 138,450,000 dwellings in 2018.24

Australia had a population of 25.1 million as of 2019, and about 5,429 housing co-operatives with about 1,029,008 members. Their total housing stock in 2011 was 7,760,322 dwellings.25

Japan, according to CHI, has about 30 housing co-operatives, and 1,014,830 members.26

21 https://www.thenews.coop/119989/topic/development/worlds-co-operatively-minded-countries/ ;; https://4bfebv17goxj464grl4a02gz-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/drupal/Profiles%20of%20a%20mov ement%20final%20web%20ISBN.pdf

22https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/data-research-maps/toronto-progress-portal/world-rankings-for-toronto/pwcs -building-better-cities/

23 https://www.housinginternational.coop/co-ops/canada/

24 https://www.housinginternational.coop/co-ops/united-states-of-america/ 25 https://www.housinginternational.coop/co-ops/australia/

26 https://www.housinginternational.coop/co-ops/japan/

20

Often, hundreds of empty apartments will be collectively owned by companies in a city, however simply sit unused for months to years. In Barcelona, Spain, the city demanded that the fourteen companies that own the majority of their rental housing find tenants for these units, and otherwise they will be rented by the city as public housing to lower-income tenants. Following about a year or two of stagnancy after the financial crisis in 2007, some companies that own multiple properties decided to leave units unoccupied until the market revived. London, England s imilarly had about 22,000 vacant homes in 2018. Reviving empty apartments and housing units to make them accessible to lower-income individuals could provide housing to many people at a lower cost, as these units are already built and require no extra costs on fabrication.27 However, as explored throughout this paper, it is not nearly as easy as outlining the issue of homelessness in Toronto. Factors such as an excessive amount of regulated intervention, a lack of supply/resources, and a lack of rehabilitative services combined with housing must be addressed as well.

As stated previously, a multitude of countries worldwide have been implementing low cost housing units made off-site in the simplistic form of stackable containers that act as small compound homes. In this way, more affordable housing can be applied to larger projects without increasing the cost of the development of these small homes a large amount. It adds incentive to add more affordable housing units to a housing initiative, and is extremely low-budget, making it more sustainable. However, as with modular housing, we have not seen an extreme amount of improvement in the fundamental root of the issue.

Unconventional units have, in this way, been converted into housing. An example of this can be shown in Berkshire, England. In the town of Reading, an increasing amount of local authorities have been placing homeless families in shipping containers converted into temporary h ousing due to their national shortage of social housing at this time. In 2017, about 28 modular homes and temporary housing buildings were constructed from stacked containers of sheet steel and timber to act as temporary accommodation until something more permanent could be found.28

In San Francisco, CA, a non-profit organization known as “Lava Mae” launched, and converted a San Francisco city bus into a transportable shower unit/trailer, that has allowed over 2,400 homeless people to have access to hygiene services and “pop-up care villages”, and has been met with great success as well as the desire to expand a similar project to Los Angeles.29

27https://www.thelondoneconomic.com/property/barcelona-tells-landlords-find-tenants-or-we-will-rent-your-property-as -affordable-housing/20/07/#.XysME3SyKt4.facebook

28https://inews.co.uk/opinion/ive-been-living-in-shipping-container-style-housing-for-two-years-the-mould-is-making-m y-son-ill-565563

29 https://lavamaex.org/

21

London, England, has something similar with the “Buses4Homeless” NGO30, which have used decommissioned buses and other such vehicles and repurposed them into dining areas, health centres, and shelters for homeless people in the city. Along with this, homeless individuals taking shelter in the 16 sleeping pods, as well as taking care of basic needs through these refurbished buses also have the option to take a three month program. As stated in the internet platform for “Buses4Homeless”, their primary goals are [to]:

1) Help Identify and Overcome the issues that lead to [individuals] being homeless 2) Teach them Soft and Vocational skills

3) Engage them into Apprenticeships / Further Training

4) Help secure Employment / create Small Businesses

5) Re-engage them back into the community through housing, support and long term mentorship Something similar to this model could absolutely be applied to temporary housing, or basic

shelter, in Canada as well, at a lower cost than what constructing and creating entirely new housing units would take.

In the Upper West Side of New York, three local hotels were turned into temporary homeless shelters in wake of COVID-19. Nearly 300 individuals were moved into one of these hotels as a shelter due to overcrowding in homeless shelters in other areas of the city. Though some individuals living in the areas took issue with witnessing displays of drug use, or inappropriate behaviour, the overall use of hotels as supportive housing can be considered as successful.31

Even in the city of Toronto itself, in mid-July 2020, a new affordable housing project was adopted in Kensington Market, where a former parking lot was repurposed in order to build a 22-unit rental building, as owned and operated by the organization St. Clare’s Multifaith Housing Society.32 The city also attempted something similar to New York, where shelter hotels are being considered as a conduit for reducing homelessness. The House of Friendship, an organization in the city, also claims that they have been planning to strategize and create a hotel-like shelter with an added on medical clinic to replace the currently existing facility they have in another area.33

30 https://buses4homeless.org/all-causes/ 31https://www.msn.com/en-us/travel/news/homeless-shelters-in-hotels-divide-residents-on-upper-west-side/ar-BB17T ksa

32https://www.toronto.com/news-story/10073333-new-affordable-housing-project-opens-in-toronto-s-kensington-mark et/

33 https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-could-shelter-hotels-be-a-model-for-addressing-homelessness

22

All in all, the final research report for the Social Economy Suite program, as provided by The University of Saskatchewan and their Centre for the Study of Co-operatives, summed up the intentions of cooperative housing especially well:

“The social economy in Northern Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan [as well as the rest of Canada] is strong and diverse. Co-operatives are the dominant organizational form, but not for profit associations and social enterprises are significant players as well. Social economy organizations have built and strengthened rural and remote rural communities, and contributed important services in urban centres. Traditionally marginalized communities have found inclusion through social economy –organizations focused on the disability community, newcomers and others often disadvantaged in the employment market.”34

Social economy as a term may be limiting, and imposing economic boundaries on social relations, in particular as it pertains to Indigenous communities. Housing vulnerable populations in Toronto is far from impossible. Programs similar to the aforementioned initiatives, and the usage of already existing buildings, can only aid in making sheltering all of the vulnerable people in Ontario a more realistic goal, and at a more affordable cost than the alternative.

But as stated by Richard Dunwoody, “One must remedy and address individual issues. Deconstruct and work to solve them. You must be involved in discussion but that is not a solution, that is a statement. Outside of proposals, initiatives must show genuine results.”

Something that the COVID-19 virus has observably shown to society in a multitude of nations is that affordable housing, and accessible shelter, is crucial to the survival of so many vulnerable individuals, and communities spanning across the globe. This is why it is fundamentally necessary to remain not only informed and aware, but proactive. To summarize in a quote by Cathy Crowe, “The only thing homeless people have in common; it’s not addiction, it’s not mental illness, it’s that they have been dehoused. With COVID, they have no place to go because of the crowdedness of the city and its development; those are the most vulnerable people. They are the ones that are going to get ill.” It is essential to remain rooted in empathy, and open to dialogue in order to protect the most vulnerable in our community.

34https://usaskstudies.coop/documents/social-economy-reports-and-newsltrs/final-report-february-2012.pdf

Fatima Shrafat is a student at the University of Ottawa who specializes in housing research with a focus on social and economic disadvantage. She has been published in Canadian Dimension magazine and aims to increase human rights advocacy through her writing.

Play a Role in Shaping Canada’s Future

Together, let’s build a dynamic voice for progressive policy in Canada.

What’s New

Current Initiatives

The Canadian Flag

What are Your Thoughts About the Canadian Flag? Invitation to a National Conversation

Send us your thoughts in words, pictures or videos. What do you feel the flag stands for and what does it mean to you? Keep the words to under 150 and the videos to under 60 seconds and we'll post them. The only requirements are that you be respectful and you post in English or French so they can have the widest reach.

Please send them to: Flag Project Coordinator, Pearson Centre: info@thepearsoncentre.ca

Learn more.

New Members of Parliament

New Members of Parliament share their thoughts and plans for the upcoming year.

Learn more.

Progressive Podium

An innovative series of policy proposals that are bold, progressive, innovative and future-focused.

Learn more.