February 13, 2021

“A National Standard for SENIORS’ CARE” (Pearson Report; Hunsley)

By Terrance Hunsley, Senior Fellow, The Pearson Centre

The Pearson Centre commissioned this report by Senior Fellow Terrance Hunsley. The views expressed here are those of Mr. Hunsley. This is published to inspire dialogue on an important Canadian public policy, and was the subject of a Pearson webinar on February 11, now available on our YouTube channel. It was also submitted to the federal government as part of its pre-budget consultations. This is major issue in Election 2021 that all parties need to address.

We want to thank two sponsors for this report: the Canadian Labour Congress and the Ontario Nurses Association.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

This paper proposes a National Standard and federal leadership to make continuing health care in institutions, homes and communities universally accessible, affordable and meeting acceptable standards.

A new National Health Accord is recommended, bringing federal contributions to fifty percent of national health care costs which would also permit funding for pharmacare and mental health services. We welcome discussion and comments on the paper. Please copy any comments to the author at terrancehunsley@gmail.com.

The Pearson Centre wishes to acknowledge two sponsors for this report: the Canadian Labour Congress and the Ontario Nurses Association. While we welcome sponsors to assist with our projects, the views expressed in such reports are those of the author.

Table of Contents

The Rationale for a National Standard

Wording of a National Standard for Seniors’ Care

How to Achieve the Goal

Federal Leadership

Other Governments

Comments on Costs and Benefits

Current Spending on Seniors

Health Transfer

Seniors’ Wealth

Post-COVID opportunities

A Broader Social Accounting System

Conclusion

Appendices:

Summarized criticisms of the current system

Summarized recommendations for improvements

Other Sources

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Canada’s seniors are for the most part, healthy and enjoying good lives. But those whose health is impaired by serious physical conditions or cognitive decline, are vulnerable and in need of care. So far, they have relied on a health care system which is designed around hospitals and doctors whose patients come to them from a large catchment area. Continuing care services grew out of this institutional model as a grudging afterthought.

This year, COVID-19 exposed shocking inadequacies in continuing care services. Many people have died and more are dying. And when the pandemic is over, hundreds of thousands of people, and those who love them and those who provide service and care, will still be living in precarious situations.

As Sharon Sholzberg Gray wrote before the pandemic:

Transformative change from a hospital and physician-based medicare system is essential if our health system is to cope with an aging population and address the needs of underserved population groups in our country, for example, people with mental and physical health challenges, children with special needs, and those requiring palliative care services – whether seniors or not[i]

The Canadian Association of Retired Persons (CARP) points out that:

Residential care facilities …have long been plagued by …severe underfunding, chronic understaffing, outdated facilities…these challenges existed before COVID-19 and will continue to threaten the lives of vulnerable residents without immediate action.[ii]

As Hassan Yussuf of the Canadian Labour Congress put it,

…we do have to question why it took the global crisis, hundreds of deaths and intervention by the armed forces for the message to finally get through: our system is broken.[iii]

But the problem does not end there. Statistics Canada points out that the population most likely to need care is in process of tripling over the next 30 years:

Between 2019 and 2049, the number of Canadians over the age of 85 is projected to grow from 844,000 to 2,630,000[iv]

Even this is probably an underestimate, since it does not factor in the increased need for care which will be a legacy of COVID, and it assumes that the hours of unpaid care by friends and family will also triple.

The COVID crisis also revealed that the provision of care services has been largely on the backs of precarious workers, especially women, often immigrants and racialized minorities. Across the country, there are retirement residences and long term care homes where nurses, personal support workers, dining room and kitchen staff and cleaners are immigrant and racialized workers; many working two or more shifts a day and being paid as part-time. They are low-paid, do not receive normal employment benefits, have no security, and work in conditions which emerging research indicates are stressful and dangerous[v]. Their risks include contracting diseases, physical injuries, muscle and tendon strains, stress, and violence.

The denial of wages and working conditions commensurate with the importance of the work is due not only to exploitative employers, but also to governments which establish fee structures and service standards and regulate working conditions. For those who may be unclear about systemic discrimination, this is a clear example. Profiteering, substandard service and exploitation were built into the continuing care financing model, instead of responding in a positive way to the needs of an aging society. It may be indicative that the Ontario Nurses Association has initiated a charter challenge to recent provincial legislation which removes the bargaining rights of health care workers in hospitals, long term care, home and community care. [vi] And against objections from many citizen’s groups, the Ontario government passed into law on November 20, 2020, an act intended to protect long term care operators from law suits related to residents contracting and dying from COVID because of substandard conditions and neglect.[vii]

Residential long-term care homes have become the main locus for care, even though several other countries have long ago shifted the balance toward care in the home and community. With escalating costs, provincial governments are trying to pivot toward more services in homes (including retirement homes), which is where most people prefer. They are trying to limit expenditures on residential care, and on costs of hospital patients who could be moved to residential care. These are valid objectives but attaining them requires substantially more investment in home and community services, as well as cleaning up the mess, and backlog, in residential care. It means re-envisioning the care model, and ensuring that standards of care are significantly improved and enforced. It will not be an easy fix.

As the proportion of elderly receiving care in private homes increases, the care required will be more complex and demanding. Most care in the home is still provided by unpaid family and friends. According to Statistics Canada, about 5.4 million Canadians provide care for older family members or friends. Their total hours of unpaid care far exceed the hours of paid care. When the numbers of elderly triple, the pressure and stress on caregivers and families will also triple.

Canada has a serious problem. It has been well-studied, well-documented, and thoroughly reported to governments. Highlights of the research are presented in the Appendices. This paper focuses on how to deal with the problem at the national level, recognizing that the bulk of the activity will be delivered at the provincial and local levels.

Care services need to support health, fitness and social well-being. A proactive and comprehensive service system is required which involves communities as well as individuals, families and caregivers. Personal support, social support networks, nutrition, fitness, recreation, safe and welcoming neighbourhoods, accessible transportation, all contribute to maintaining health and extending quality of life. The quality, affordability, and accessibility of services needs to be improved.

As Leonard Cohen might have put it, “The heart has got to open in a fundamental way.[viii]”

- Rationale for a National Standard

The federal government has never acknowledged a responsibility for proportionate financial responsibility in this expanding area of health care need. Nor have provincial governments been willing to direct appropriate funding to support high quality services. Political inertia, ideology, and embedded fiscal competition between governments have undermined action.

The systemic change that is required needs sustained involvement of a Canadian society which does not accept patchwork. A national goal, enshrined in federal legislation, with provision for constant monitoring and reporting, would reinforce an essential common purpose.

Upon enactment of the standard in Parliament, the Prime Minister should invite governments, institutions, retirement and care residences, businesses, professional associations, unions, community associations and service organizations, to formally ratify and subscribe to the standard. Those who do would undertake to report annually to their constituents on their observations as well as their own contribution to care-friendly communities.

- Potential Wording of a National Standard for Seniors’ Care

Canada commits that every person requiring care will have a right to high-quality, accessible and affordable care and support services, including supportive accommodation when required. They will also have health-sustaining access to a nutritious diet, recreation, exercise and social involvement, and will have flexibility in planning their living and service arrangements.

Seniors who wish to live at home as long as possible will receive supportive health and personal care and seamless access to assisted living and more structured care when appropriate, all within the context of caring communities.

Every person over the age of 75 will be contacted every year to be provided with information on options to access care, improve health, prevent debilitating incidents, and preserve quality of life.

People who provide care, regardless of the location of service, will be well-trained and provided equitable wages and working conditions, based on occupations doing work of comparable value and challenge. The services provided will meet standards recommended by competent expert agencies, including favourable assessments by care recipients and families.

Families and informal support givers will be provided with assistance and resources required for that support and will be adequately compensated and relieved when care requires extensive time commitments or loss of income.

Canada will secure its ability to respond to future emergencies by maintaining an adequate supply of appropriate equipment and production capacity to supply all care locations immediately.

Annual reports will be made to Parliament by Statistics Canada and the Canadian Institute for Health Information, and will include regular surveys of care recipients, formal and informal care providers, and relevant community organizations. They will include availability of a wide range of care services, assessments of quality of care, access and cost measures, with comparative international indicators.

- How to Achieve the Standard

Federal Leadership

Federal leadership should be exercised by enacting the standard in legislation and providing a long-term funding commitment to other governments, as well as substantial new funding for community action, and a national care industry council. To implement these:

a) The federal government should propose a new National Health Accord, with a funding commitment extending over the next thirty years. The government may wish for the new accord to cover, besides continuing care, additional funding for pharmacare and mental health services.

b) The federal contribution to provincial health care costs is currently about $60 Billion, or roughly 35% of $173 Billion total[ix]. It is appropriate for overall federal funding to approach half of national public health care expenditures, including provincial/territorial costs, indigenous health care, veterans care, research support, the services of federal health agencies, the value of health-related tax credits, and support for community action. We interpret this to mean an increase in funding of about $20 Billion per year, adjusted annually in line with the national average increase. It could be mostly through the Canada Health Transfer, with some funds reserved for community action. The new funding should be put in place immediately, with provisional funds available as negotiations proceed on conditions and accountability.

The federal government may wish to amend the Canada Health Act to broaden the definition of health services to cover care wherever delivered. This could prove difficult because the range of services that may be required go beyond normal definitions of health services – housekeeping, home maintenance, shopping, etc. Having them prescribed by a medical professional could also become a burdensome task. Alternatively, as in the case of the 2004 Health Accord under Prime Minister Paul Martin, the Accord conditions could be linked directly to accomplishing the goal of the new financing while also affirming the principles of the Canada Health Act.

c) The federal government should establish a national Care Industry Council, with a board equally representative of consumers, employers, and workers. Among its duties, the council would be responsible for:

– recommending reference wages, and reporting annually on overall developments in the sector, including wages and working conditions,

– recommending to appropriate authorities, education requirements, training and re-skilling programs, relevant study loans and conditions,

– working with research funding authorities to support development and deployment of innovative technology and up-skilling of workers.

d) Innovative care configurations, housing options and caring neighbourhoods should be encouraged. Federal funding streams provided by agencies and departments such as Health Canada, Canada Mortgage and Housing, Infrastructure Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada, the Minister for Seniors, Industry Canada, and research funding agencies should support:

- New configurations of integrated care, care delivery and mobile services centred in communities. Examples include expanding multidisciplinary and wholistic care through community health centres and nurse-practitioner-led community clinics. Mobile care services are an obvious place to promote transition to renewable technology vehicles and innovative application of technology.

- Community-based, non-profit supportive housing initiatives for care residences, cooperative housing and collective living, assisted living and innovative service clusters. New services and housing options could be integrated with existing structures such as schools, libraries, community centres, churches, and linked with public or community nonprofit transportation.

- Community organizations that wish to develop innovative programs providing care and social inclusion for older seniors to ensure access to personal support, social participation, nutritious food, exercise, and safe neighbourhoods.

e) Statistics Canada and the Canadian Institute for Health Information should report annually to Parliament, using the federal constitutional power for national statistics. They should report on:

- the experience of people using care, including those attempting to access it in homes, the community, or care residences;

- the costs which are carried by individuals;

- the experiences of families and informal care providers;

- the experiences of municipalities and communities in becoming caring communities;

- performance indicators for service systems, including service delivery standards, numbers and deployment of health, personal service and other support workers, their salaries and working conditions;

- returns on public investment through received tax revenues from consumers and providers, accrued value of infrastructure, and estimated spinoff economic benefits.

Other governments

With federal assistance, provincial, territorial and indigenous governments will need to upgrade the availability, quality, reliability and flexibility of health, social and community support systems, as well as labour standards in the sector. They have primary jurisdiction to govern and regulate health and social services, regulate work and safety standards, establish funding and delivery methods, monitor and evaluate. The dominant health service model needs to be adapted to include a dynamic community and neighbourhood role.

Municipal governments which ratify the national standard should integrate it into their programs and activities, ensuring an annual appraisal of care friendliness of the municipality, service needs and community supports. The municipality may also be in the best place to ensure the integration of a broad spectrum of health and social service needs assessment and provision, with the active involvement of the senior and the community.

Local community service coalitions such as United Ways/Centraides, with research support from social planning councils, could partner with the municipality in this, in order that the widespread planning and delivery of health and social services through “silo” bureaucratic systems finally come to an end.

Service delivery organizations should also explore the potential to employ healthy retirees for care occupations, or to engage them in voluntary service. Exploratory work by Dr. Leroy Stone shows that the potential in the post-retirement age range is substantial and growing.[x]

Community Organizations

In cooperation with governments, community organizations and associations should create and nourish caring neighbourhoods. Several municipalities have recently been promoting the concept of “fifteen minute neighbourhoods,” where all services should be within a fifteen minute walk. – but health system planners have for the most part, ignored that. These organizations should encourage community-based holistic care, housing and accommodation options, flexible transportation options, safe walking environments, assistance for home maintenance, renovations and accessibility, social connections, nutritional programs, exercise, rehabilitation, disability prevention and abatement, recreation, and other health-enhancing programs. Initiatives can be public, private and nonprofit, neighbourhood cooperatives, co-housing, co-living and other arrangements.

- Comments on Costs and Benefits

Public Spending on Seniors

Canadians are aware that government spending to support seniors is already substantial. Canada provides a good basic income for seniors that keeps most out of poverty. Health care for seniors is also expensive, although the Canadian Institute for Health Information points out that population ageing accounts for an increase of only about 0.8% per year in health spending.

Support for seniors is part of an intergenerational social contract where each earning generation supports the public costs of children and the elderly. Despite the large size of the generation moving into retirement, the continuing and projected increase in economic productivity of the work force and the increased wealth of the country are sufficient to carry the costs. Nonetheless, the rapid increase in longevity, and especially the long-term management of many diseases through pharmaceutical advances, are resulting in costs for care that were not adequately planned for in government policy.

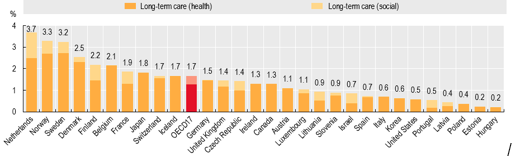

Canadians may not be aware that our country has been spending well below the OECD average on long term care. We spend about 1.3% of GDP versus the OECD average of 1.7%. We spend far below some countries such as Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands, which spend over 3%. While the number of long term care workers has increased by about 10% over the past decade, total spending on health care as a percentage of GDP has only moved from about 10.7% to about 10.8%.[xi]. Part of that difference may be attributed to Canada having had a younger population coming out of World War Two, but we also had one of the biggest baby booms and we are ageing quickly. The differential is more due to underfunding of services while permitting standards to be ignored and exploiting precarious workers. Canadian governments have also required that about thirty percent of costs be paid privately, whereas many OECD countries pay more from the public purse.

A National Institute on Ageing cost projection project[xii] suggests that the increased need, even with the shift to home-based care underway, will be a fiscally significant challenge for governments. The current cost of care – $22billion – could increase to $71billion (in constant 2019 dollars) by 2050. Even that relies on an unlikely assumption that unpaid care providers increase in proportion as well as increase the number of care hours they individually provide. So the cost will probably go higher. Yet the consequences of government not taking on the responsibility are enormous. Most seniors do not have enough income or savings to pay for their own care. Private insurance is not an option. And failing to provide adequate care is not acceptable to Canadians and would be disastrous.

Federal Health Transfer

An important underlying issue is the overall sharing between federal and provincial governments. Until 1977 the federal government provided roughly half of the money for insured health services. A new mechanism put in place at that time converted the cost-sharing formula to a combination of a transfer of taxing capability and a formula-determined unconditional cash transfer. The intent was to keep roughly the same proportionate spending. In 1984 the Canada Health Act imposed the medicare principles of universality, accessibility, comprehensiveness, portability, and public nonprofit administration. And since then, Medicare has been the most evident source of pride that Canadians have in their country.

However, unilateral federal decisions over time reduced the relative value of the federal cash transfer, now called the Canada Health Transfer. The current federal contribution is about $40Billion in cash, and an imputed value of about $20Billion for the transfer of taxing power (referred to as “tax points”).[xiii] So the federal government can claim a $60Billion contribution to total provincial/territorial spending of about $173B (in 2019). That equals about 34%. Another $78Billion is spent privately.

In addition, federal expenditures for indigenous health services, care for veterans, for health research, Health Canada, the Canada Food Inspection Agency, and tax credits for private insurance and out-of-pocket health costs, (very roughly estimated) total a bit over $20 Billion. If that amount is added to the federal contribution of $60Billion, a further increase in annual federal spending in the range of $20-25Billion with provision for future increases in line with overall health spending, would bring the federal contribution to overall public health care costs to about 50%. As suggested above, this amount could also aid to bring about some form of Pharmacare, as well as to expand the availability of mental health services, two other federal priorities.

Seniors’ Wealth

To be sure, many seniors are not wholly dependent on the state and they are currently spending their savings and pension funds, paying taxes and contributing to local economies. Most of their older years are spent in relatively good health and independence. But they were never told they would have to pay for their own health care, and most do not have savings to do so.

That said, the seniors’ generation will be transferring more than $1Trillion to the next generation through inheritances over the next twenty years.[xiv] These transfers will reinforce existing inequalities of wealth unless a more progressive income tax system with progressive estate and wealth taxes is established. The federal government should proceed to increase tax revenues through these mechanisms.

Post-COVID Opportunities

Emerging from COVID there will be a need for substantial fiscal stimulus. Governments may choose to stimulate enterprises that are selling in Canadian and international markets. The gamble is to choose winners and hope that, if they win, the economic benefits and jobs stay in Canada. An alternative is to support consumption of goods and services which are needed and locally provided. Investments in continuing care and environmental improvement are in this category. The spinoff economic benefits make their way directly into the Canadian economy, creating jobs and business opportunities, while the markets choose the winners.

Governments should also consider the asset-building dimension of investment in community facilities and residential care. Private equity funds – many from other countries such as China – are currently buying into the residential care market. This is not only because their profits have been very high, but also because the increasing value of the properties is a major capital gain. Governments have turned a blind eye to this under-taxed wealth-accumulating process, as documented by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. [xv] Creative financing policies such as partial equity financing could enable community organizations, community land trusts, or municipalities to accumulate real estate equity which in turn can be reinvested in the community.

Individual Canadians also need to consider how they will spend their older years and how they might mitigate the costs of infirmity. They can work within their communities to develop more home- and community-based service systems and accommodation options. For example, there could be community-based alternatives to commercial assisted living accommodations and retirement homes. Nonprofit community-based developments or cooperatives could also provide residents with options to invest some of their housing equity.

Innovative solutions can be found and scaled up, which create economies and economic opportunity. There is a need for new technology to improve service delivery and reduce costs, new ways to integrate care into institutional and community structures in ways which extend independent living.

From an economic perspective, the investment in services, housing and transportation options can create good employment in health, social and recreational services, as well as in industries which cater to seniors. New health and assistive technology will find large markets, not only in Canada but internationally. New accommodation will stimulate small business and improve environmental stewardship. Friendlier, happier, more accessible communities will be vital for the dispersed work and living patterns of the future. Indeed, it is likely that working from home will entice more seniors to extend their involvement in the labour market, which will be good for them and for the economy.

This is a good time to commit to a transformation in health care. For example, COVID has shown us that a very significant portion of ambulatory health care can be delivered remotely, with equal effectiveness and savings for consumers. With experimentation already underway in most provinces, there is an excellent opportunity to shift health spending in ways that can make it more efficient, more holistic, and a better experience for consumers.

A Broader Social Accounting System

Finally, a comment on the need for a new kind of social accounting: Many initiatives can improve people’s health and decrease health system costs. But “silo” budget systems, which characterize most public health and social service bureaucracies, do not permit credits to be accumulated where money is saved. For example, if a city develops a way to keep residential sidewalks clear of ice, thousands of seniors would be prevented from falling and injuring themselves. That would save hospitals and medical services millions of dollars. In turn it could delay for some years the need for those people to require continuing care – more millions in savings. So how does the city maintenance department get their share of the health system savings?

In theory, governments can decide centrally to redeploy funds. In reality it does not happen. We need a social accounting system which could perhaps be inspired by the “cap and trade” system, to be able to incentivize prevention and health-promoting activities.

- Conclusion

The reports summarized in the Appendices make it clear that Canada has permitted a big problem to develop in the care system. The problems were exposed by COVID but were well-known and basically ignored before that.

Canadian governments at all levels are culpable in this regard, and an exploitative and profitable industry has developed to provide inadequate care to the most vulnerable.

A clear commitment to do better, to start immediately, and to engage the country, is needed.

- Appendices

Summarized criticisms of the current system

The inadequacies of current services were well-documented before COVID. Thorough research has been published and brought to the attention of governments.

Indeed, there were actions underway to try to bring improvements. The federal government modestly increased the CHT in 2017 to stimulate improved mental health and home care services. To date I have seen no reports to the public on improvements.

Following are highlights from the existing research:

a) Lack of data: The information available to the public, and to seniors, is inadequate.

There is no clear consensus on the number of older Canadians who are actively receiving care or services across the long-term care continuum, neither is there a consensus on the proportion of Canadians receiving care in various settings, such as care in the home, care in community facilities, care in assisted living facilities, care in long term care facilities.[xvi]

Indeed, long-standing reports, such as the Romanow (2002) and Kirby (2003) reports have pointed out that clients, caregivers, and many health and social care providers do not know which services are publicly funded, under what conditions, and the associated assessment process for determining eligibility.

There are no standardized Canada-wide data on the costs of home care or nursing homes, nor on the range and character of services provided. Both the OECD and CIHI produce annual data on health care expenditures but … both series have substantial data quality issues[xvii]

b) Lack of emergency planning. According to recent media reports on long term care, and despite lessons apparently learned from previous pandemics, there were no provisions in place to protect the public from a pandemic-no emergency protocols, no stocks of emergency supplies. With the exception of British Columbia, in the long-term care homes, despite clear warnings from experts, there were no provisions for adjusting staffing to maintain capacity to provide essential care. Indeed, many care workers had to work in two or more part-time jobs with no sick leave, because of policies to minimize business expenses.

c) The services were known to be inadequate.

“We were in a staffing crisis going into COVID” (Minister of Long Term Care Merrilee Fullerton, on TVO, Nov 25, 2020)

Inadequate services have become the norm in many parts of the country, with service providers not being appropriately monitored, and reports of inadequate, abusive and neglectful services being routinely ignored.[xviii]

A data analysis of the most serious breaches of Ontario’s long-term care home safety legislation reveals that six in seven care homes are repeat offenders, and there are virtually no consequences for homes that break that law repeatedly.

CBC Marketplace reviewed 10,000 inspection reports and found over 30,000 “written notices,” or violations of the Long-Term Care Homes Act and Regulations (LTCHA), between 2015 and 2019 inclusive. The LTCHA sets out minimum safety standards that every care home in Ontario must meet. Marketplace isolated 21 violation codes for some of the most serious or dangerous offences, including abuse, inadequate infection control, unsafe medication storage, inadequate hydration, and poor skin and wound care, among others. The analysis found that of the 632 homes in the Ontario database, 538 — or 85 per cent — were repeat offenders.

d) Discriminatory practice with waiting lists

For those who need long-term care, there are long waiting lists for subsidized facilities, while care in private facilities can be unaffordable.

… the cost of care can far exceed median incomes and its duration can be many years.[xix]

It may be argued that provincial governments are violating charter equality rights in their use of waiting lists to ration services and reduce costs. There is a documented selection bias favouring people who are admitted to hospitals (a desire to get them out of the costly hospital bed), while for many others, the wait time exceeds their remaining life expectancy.

e) Canada has been spending less than similar countries on long term care.

Long-term care expenditure (health and social components) by government and compulsory insurance schemes, as a share of GDP, 2017 (or nearest year)

Note: The OECD average only includes 17 countries that report health and social LTC. Access the data behind the graph

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2020.

Out-of-pocket costs (the share of the costs that are left after accounting for public support) of home care can be very high for older people with severe needs, while institutional care for the same individuals is often more affordable. This suggests that public support is not well-aligned with ageing-in-place policies.[xx]

f) The numbers needing care are growing rapidly.

In Canada in 2019, 2.2%, or over 770,000, of the population consisted of adults aged 85 and older. When the oldest boomers reach 85 in 2031, this cohort will increase to 4% or over 1.25 million; when the youngest boomers reach this milestone in 2051, a further increase to 5.7%, or about 2.7 million, is expected. Financing the retirement years for these Canadians will be a growing challenge as life expectancy increases. In particular, few Canadians die in the year actuarial tables predict, because, while actuarial tables can accurately predict population level mortality, at the individual level, they are less accurate. This creates uncertainty and a real risk of outliving one’s money. In response, Canadians often reduce expenditure on the necessities of life, reducing their quality of life and leaving “too much” in savings or in their estate when they die.

In 2016, it was noted that 53.8% of older households in need of core housing were women who lived alone. [xxi]

g) The stress on informal caregivers, families and care workers was already becoming a major issue.

The greater supply of home care is still not meeting the current needs of Ontarians and their caregivers. With the types of clients being supported with publicly funded home care becoming collectively more cognitively impaired, more functionally disabled, and sicker, the corresponding levels of their caregivers reporting experiencing distress, anger, or depression related to their role and/or were unable to continue their caregiving activities has risen as well. Health Quality Ontario recently reported that 44% of its publicly supported home care clients with an unpaid caregiver in 2015/2016 reported these concerns compared to 33% in 2013/2014 and 15.6% in 2009/2010.[xxii]

Long-term care is a labour intensive sector, comprised mainly of female, often foreign-born personal support workers (PSWs) whose jobs are generally low-paying, physically and emotionally exhausting, and rarely structured for career advancement.[xxiii]

h) Private investors are making large profits and large capital gains in this sector, despite low levels of service.

Andrew Longhurst, for CCPA, has illustrated how lucrative the private independent and assisted living market is, with living costs exceeding the capacity of most seniors. Many of the private providers are also providers of publicly subsidized care. They gain important leverage over government when they can threaten, as they did in BC, to shut down facilities and evict vulnerable seniors if their fees are not increased.

…financial services giant UBS identifies Canada as the second most attractive market for investing in independent living, assisted living and long-term care facilities, behind Japan and slightly ahead of the US.43 For-profit assisted living operators can expect a 30 to 40 per cent operating margin compared to 15 to 25 per cent in long-term care.

Ultimately, investors are interested in the real estate assets. As an industry publication notes, “Buying into a seniors’ home, you’re really investing in a business backed by real estate [xxiv]”

Summarized recommendations for improvements

a) Enabling evidence-informed integrated person-centred systems of long-term care, accounting for the expressed needs and desires of Canadians.

b) Provision for needs that vary by geography, urban level, social characteristics, resource levels. An active community role has been recommended.

c) Planning around the person, not the bureaucracy. One strength of Canadian medicare is the right to access a wide range of health services by going to our doctor. We don’t have to apply to anonymous bureaucracies.

d) The Canadian Association of Retired People (CARP) suggests:

Minimum staffing levels that include more interdisciplinary, full time staff to improve continuity of care

Training and education to support ongoing professional development and specialization for care workers, managers and boards

Innovative solutions that will provide increased space for quarantines, access to rapid testing, and personal protective equipment

Funding for long-term care home renewal projects, including HVAC, floor and window replacements, water and sewer line replacement, and building upgrades (additional bathrooms, reconfiguring 4-bedroom wards)

Funding for transformative and compassionate dementia care model in long-term care facilities

Fully funded high-dose flu vaccines and expansion of pneumococcal coverage for Canadians over 65 in congregate settings[xxv]

e) Housing alternatives should be provided.

Older adults across the socio-economic spectrum could benefit from a variety of housing to support healthy ageing in the places of their choice.

An age-friendly community is defined as one that recognizes the great diversity amongst older persons, promotes their inclusion and contributions in all areas of community life, respects their decisions and lifestyle choices, and anticipates and responds flexibly to ageing-related needs and preferences. Essentially, they are places that encourage active ageing by optimizing opportunities for health, participation, and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age. [xxvi]

f) Canadian delegates were struck by the community spaces within the Danish nursing homes: fitness, library services, information and technology services, and a restaurant in the nursing home were also available for community members.[xxvii]

g) When older adults decide to or are forced to stop driving, it is imperative to ensure that various alternative and accessible transportation options are available. Therefore, programs that help older adults maintain their independence and mobility and allow them to travel wherever they want to go in the community safely, and in an accessible and affordable way, are extremely important. [xxviii]

h) Canadians who are hospitalized for falls remain hospitalized for an average of 14.3 days, while the average length of hospital stay in general is 7.5 days. In Canada, between 20% to 30% of older adults fall annually, making it one of the most common preventable health care issues for older Canadians. [xxix]

i) Another focus for public policy is the value of better supporting, encouraging, and enabling physical activity among seniors, potentially delaying or even eliminating the prevalence of disability for many seniors.

Research supports the very positive impact of nutrition and exercise capacity on improving the activities of daily living – including reablement programs that help seniors to regain functional capacity[xxx].

j) Age-friendly communities are an example of a relevant initiative, as it focuses on the development of communities that prioritize the health and well-being of people of all ages and across the life course[xxxi].

k) Outcomes reporting should include …

- Quality of long-term care as perceived by the recipient and their close family members

- Financial burdens borne directly by individuals and their families

- Availability of long-term care (e.g., in terms of waiting lists, difficulty finding a personal care assistant to hire)[xxxii]

l) Enabling evidence-informed integrated person-centred systems of long-term care, accounting for the expressed needs and desires of Canadians.

… Supporting system sustainability and stewardship through improved financing arrangements, a strong health care workforce, and enabling technologies.

.…Promoting the further adoption of standardized assessments and common metrics to ensure the provision of consistent and high-quality care no matter where Canadians need it.

… Using policy to enable care by presenting governments with an evidence-informed path towards needed reforms.

… There is “a strong need for a clearly defined publicly-funded “basket of services” that recognizes that non-clinical supports such as homemaking, meal preparation, supportive housing, transportation and respite are often essential to supporting an individual at home”[xxxiii].

m) Age Friendly Communities:

Community support and health services should be tailored to older persons’ needs.

While this evidence brief focuses on the AFC domain related to development of age-friendly buildings and spaces, other briefs focus on the other AFC domains, such as respect and social inclusion, social participation, communication and information, civic participation and employment, transportation, housing, and community support and health services.[xxxiv]

n) With more than 6.3 million Canadians currently living in rural areas, which tend to be ageing faster than in urban areas, ensuring that older rural dwelling Canadians are able to age-in-place will need to be a focus of any efforts to improve the accessibility of Canadian communities.

o) Only 12% of older adults have adequate health literacy skills to support them in making basic health-related decisions. Alternative methods of communicating need to be found.

p) Federal Government response to the Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities (HUMA) report:

.. the evidence showing that healthcare utilization and healthcare costs can be significantly reduced when seniors are socially engaged, physically active and have access to nutritional education and supports. Research shows that fostering resilience in seniors can be supported through a range of strategies, including:

- fostering social connectedness and civic engagement,

- building skills that increase positive emotions and more effective coping,

- supporting lifestyle changes that increase access to physical activities, better nutrition, etc.,

- providing technology-based interventions for home bound seniors,

- enhancing primary and secondary prevention of chronic conditions; and

- increasing problem-solving capacity.[xxxv]

[i] Sharon Sholzberg Gray, http://thepearsoncentre.ca/platform/medicares-unfinished-business-a-proposal-for-a-home-and-continuing-care-program-for-canada/

[ii] The Canadian Association of Retired People: https://www.carp.ca/longtermcare/

[iii] Hassan Yussuf, CLC, in National Newswatch, June, 2020

[iv] National Institute on Ageing; https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c2fa7b03917eed9b5a436d8/t/5d9ddfbb353e453a7a90800b/1570627515997/The%2BFuture%2BCost_FINAL.pdf(The Future Cost of Long Term Care, 2019)

[v]https://research.sehc.com/SEHCResearch/media/Research_Centre/pdfs/HCE-108-179-2019-01-21-ROTR-PSW-Safety-Final.pdf

[vi] https://www.ona.org/news-posts/20210115-outraged-denial-bill124/

[vii] https://www.ola.org/sites/default/files/node-files/bill/document/pdf/2020/2020-11/b218ra_e.pdf

[viii] from Democracy (is coming to the USA)

[ix] https://www.cmaj.ca/content/192/45/E1408

[x] https://onedrive.live.com/view.aspx?resid=2E1C96D82E6ACB65!1545&ithint=file%2cpptx&authkey=!ABa9gFs8sm3SyEc

[xi] OECD Health Statistics 2020

[xii] See 3 above

[xiii] https://www.cmaj.ca/content/192/45/E1408

[xiv] https://www.bmo.com/pdf/mf/prospectus/en/09-429_Retirement_Institute_Report_E_final.pdf

[xv] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives; https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/BC%20Office/2020/02/ccpa-bc_AssistedLivingInBC_full_web.pdf

[xvi] National Institute on Ageing; https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c2fa7b03917eed9b5a436d8/t/5d9de15a38dca21e46009548/1570627931078/Enabling+the+Future+Provision+of+Long-Term+Care+in+Canada.pdf

[xvii] See 3 above

[xviii] The Health Quality Council of Ontario: https://www.hqontario.ca/System-Performance/Measuring-System-Performance/Measuring-Long-Term-Care-Homes

[xix] See 6 above

[xx] See 6 above

[xxi] https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/HUMA/report-8/page-ToC

[xxvi] National Institute on Ageing Delegation to Denmark; https://www.cfn-nce.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2018-10-05_CFN-Denmark-Delegation-Paper_Longwoods-Healthcare-Quarterly.pdf

[xxvii] See 21 above

[xxix] National Institute on Ageing; https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c2fa7b03917eed9b5a436d8/t/5f7dc967ae10252b7893397f/1602079080222/NSS_2020_Third_Edition.pdf

[xxx] See 21 above

[xxxi] HUMA Parliamentary Committee; https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/HUMA/report-8/response-8512-421-370

[xxxii] See 3 above

[xxxiii] See 24 above

[xxxv] See 26 above

Other Sources Used:

Department of Gerontology, Simon Fraser University: http://www.seniorsraisingtheprofile.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/RPP-Literature-Review.pdf

Canadian Institute for Health Information: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/covid-19-rapid-response-long-term-care-snapshot-en.pdf

Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives: https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2020/11/A%20higher%20standard.pdf

Canadian Institute for Health Information: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/shp-companion-report-en.pdf

Canadian Institute for Health Information; https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/nhex-trends-narrative-report-2019-en-web.pdf

HUMA parliamentary Committee; https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HUMA/Reports/RP9727458/humarp08/humarp08-e.pdf

CBC Report on Ontario Nursing Homes; https://www.cbc.ca/news/marketplace/nursing-homes-abuse-ontario-seniors-laws-1.5770889?cmp=newsletter_CBC%20News%20Morning%20Brief_2405_213680

National Institute on Ageing; https://www.nia-ryerson.ca/covid-19-long-term-care-resources

National Institute on Ageing; https://healthyagingcore.ca/resources/enabling-future-provision-long-term-care-canada

Ontario Nurses Association; https://www.ona.org/wp-content/uploads/ona_recommendationsltccommission_20201021.pdf

Royal Society of Canada; https://rsc-src.ca/en/voices/we-must-act-now-to-prevent-second-wave-long-term-care-deaths

Aging 2.0; https://www.ab-cca.ca/public/download/documents/39490

http://www.seniorsraisingtheprofile.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/RPP-Literature-Review.pdf

https://www.cmaj.ca/content/192/45/E1408

https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/nhex-trends-narrative-report-2019-en-web.pdf

Terrance Hunsley is a former Director General of the International Centre for Prevention of Crime, Executive Director of the Canadian Council on Social Development, Executive Director of the Biotechnology Human Resources Council, Member of the Council of Science Advisors to the Federal Government, and Fellow of the Queens University School of Policy Studies